Shifting, Glances explores the macabre undercurrent to the banal and bureaucratic, the inexplicable sensation of knowing that someone at a distance is watching you, and the desire to retain anonymity and distance from another’s gaze. Featuring works by Gonzalo Fuenmayor, Hannah Lee, Yu Nishimura, and Maria Sulymenko, darker emotional undertones are made palpable within seemingly quotidien imagery and portraiture. Some works compel the viewer to adopt a voyeuristic role, while wary subjects in other works confront the viewer eye to eye. Like a wordless look shared by two people, Shifting, Glances elicits a desire to initiate something without clear implications.

Masked by fruits and foliage, Gonzalo Fuenmayor’s two portraits rendered in saturated charcoal – Flora Woman and Man With a Bowler Hat (Revisited), both 2022 – retain total anonymity, raising questions surrounding agency in a complex and continual postcolonial moment. Fuenmayor’s figures may at first appear as people-turned-commodities residual of a colonial past, yet upon further inspection their intentional obscurity feels rife with a powerfully radical potential hidden in plain sight.

The contents of Hannah Lee’s painting Swimming Pool, 2022 have an air of peaceful grandeur: a modernist home replete with a sprawling lawn and a massive aquamarine swimming pool dominate the frame, with lounging figures visible in the distance. However, the emotional resonance of Lee’s piece is far more nuanced than the sum of its motifs. Gloomy weather is rolling in across the horizon, the palette is deliberately muddied, and a soft pink towel that would typically beckon participation reads as alienating if not entirely ominous.

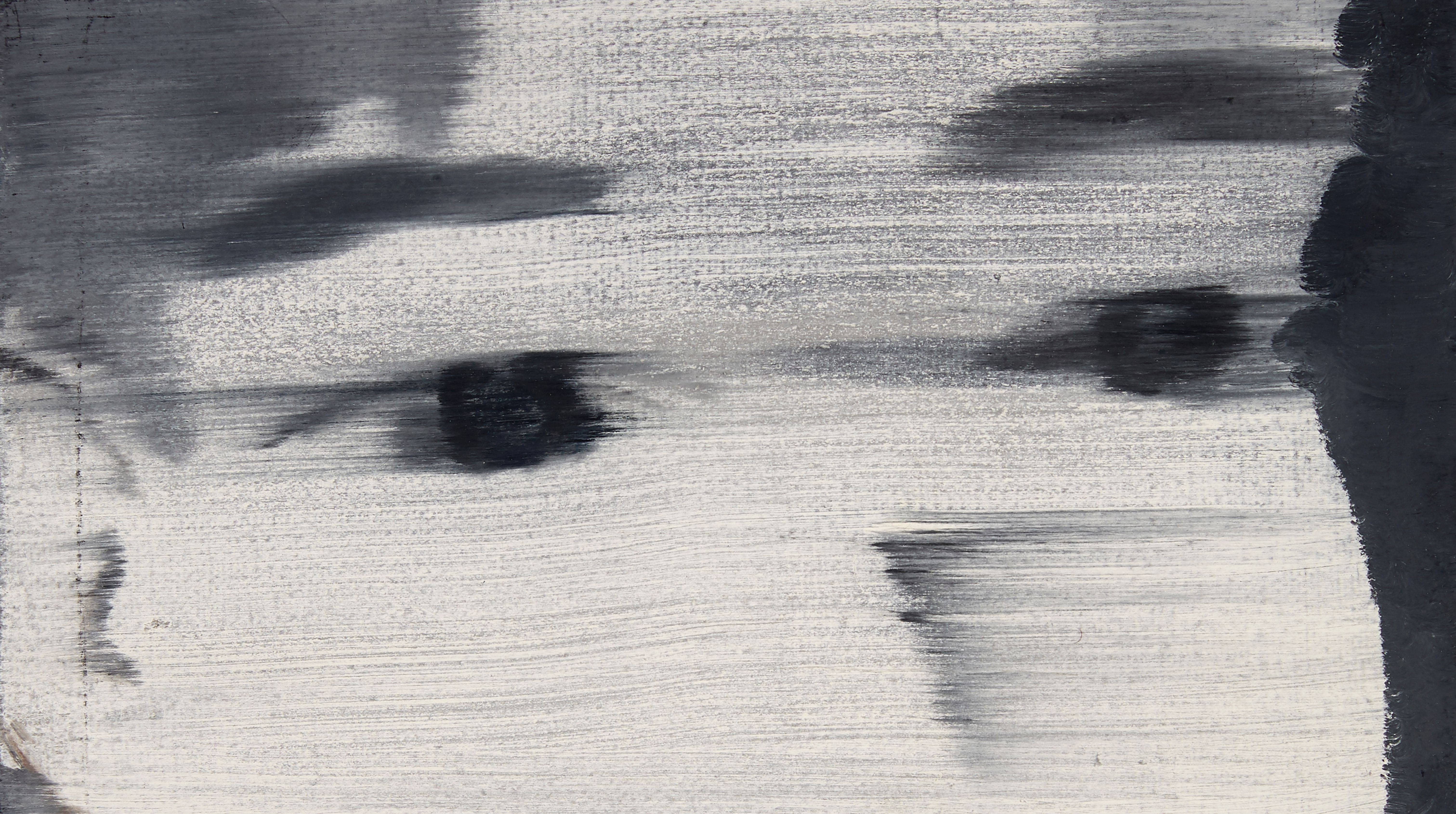

Yu Nishmura’s intimate portraiture dances between a multitude of emotions, his subjects looking back at the viewer pleadingly, with suspicion, and with feigned boredom. With a shaky, blurred line Nishimura’s characters are presented in motion and outside of the bounds of linear time. Through direct, unwavering eye contact these pieces address a viewer head on, stimulating an internal reckoning.

Maria Sulymenko’s hauntingly spare watercolor scenes are set in nonspecific locations that resemble construction sites, empty streets, suburban backyards, and the backstage of a theater production. Solitary figures stalk these abandoned areas, perhaps absorbed in a moment of existential crisis or becoming aware that they have been caught performing an unusual act. One standalone piece features three rigid figures – two are carrying the third who appears unable to walk on their own. Whether this scene is nefarious or altruistic remains uncertain, and this precise ambiguity lingers like a fog throughout Sulymenko’s depictions.